Dr. John

Original 1977 Sleevenotes:

Malcolm Rebennack came into this world direct from between the thighs of Marie Laveau on Mardi Gras morning. As soon as he started breathing, the attending physician Dr. Lolo Robicheaux gave him a spoonful of secret gumbo from a recipe inspired by Jean Lafitte. Folks, he ain't never been the same since. Once he could walk and talk Dr. Robicheaux gave him an infusion of voodoo blood mos' scociously due to the gris-gris that was laying aroun' his front door, and tol' Malcolm that he was really Dr. John, da Night Tripper. Rather thank raise a fuss about schoolin' and books, the boy they once called Malcolm decide then and there to heal people wit' his music. He immediately jumped the St. Charles streetcar to the end of the line and direct into heaven, then touched his finger to the finger of Cosimo Matassa once he arrived. I swear upon every hoodoo devil that hovered over Haiti that Dr. John has been working some mean medicine every day thereafter. Ain't no lie. I was listening to dis piece o' platter just last night and my lala wouldn't start and my yaya wouldn't stop. Now that's some heavy magic. "Course it's the way I like it".

~ Jojo Fineaux

Malcolm Rebennack as Dr. John, the Night Tripper has demonstrated on amazingly high degree of funmanship as the third generation son of the Second Line, the light New Orleans rhumba rhythm that was defined in popular music initially by Roy "Professor Longhair" Byrd, Huey "Piano" Smith, and later refined for even greater mass acceptance by Antoine "Fats" Domino. Dr. John no longer resided in New Orleans and currently devotes most of his energies to behind the scene projects in California, such as producing Van Morrison. The selections here however are as down home NOLA as red beans and rice. And they are all originals from Malcolm Rebennack. Hot as fiyo on the bayou from the Man with the Plan from the Gitgo.

~ Joe Nick Patoski

Dr. John Bio

“All my sisters married doctors”, said Dorothy Cronin Rebennack, the mother of Mac Rebennack. “ But only I had a Dr. John”. Indeed, there can be only one Malcolm Rebennack, aka “ Doctor John Creaux, the Night Tripper”. There can only be one walking repository of the storied city of New Orleans’ thriving musical history. There can be only one author of such classic songs as “ Right Place, Wrong Time”, “ Such A Night”, “Litanie Des Saintes”, and “I Walk On Gilded Splinters”. There can be only one torchbearer for the Crescent City sound as it second-lines its way into its fourth century. So Mrs. Rebennack was right -- physicians are indeed a dime a dozen in this doctor-clogged country; but a musician of her son’s caliber comes along but once in a very blue moon.

Malcolm John Rebennack Jr. was born in New Orleans a full month after term on Thanksgiving Day (November 20) 1942. Weighing a full ten pounds, Mac, as he came to be called, was born into a music-loving family in America’s most musical city. While still an infant, Rebennack starred as a model for various baby products, and showed remarkable musical ability in early childhood. By the age of three he was already hammering out melodies on the family piano, and soon exhausted the talents of the nun who was hired to give him lessons some years later. “If I play what his next lesson is going to be”, the sister complained, “he will play it right behind me, note for note”, His good-timing Aunt Andre, who it can be safe to assume had funkier taste than the nun, taught him the “Pinetop Boogie-Woogie”. My aunt was a groovy old broad”, Rebennack recalled in “Up from the Cradle of Jazz”. “I used to drive everybody mad playing it”.

Malcolm Rebennack Sr. was an appliance store owner who, as is traditional in New Orleans, also stocked the latest hit records. Thus young Mac was privy from early childhood to almost any music he wanted. Some years later the Rebennack appliance store was forced to close, and Mac lost his pipeline to the goldmine. But soon his father found work in a line even better suited to those of musical bent: PA system repair. The two Rebennacks would often be seen trundling in tandem to various nightclubs around town, bloodbucket dives with names like the Pepper Pot and the Cadillac Club. Always forbidden to enter the clubs, Mac would wait for his father to repair the system, and then peer in and dissect the musicians. It was at the Pepper Pot, in fact, and in this manner that Mac first saw Professor Longhair’s magical keyboard frolics.

At the age of seven Rebennack suffered through a bout of malaria. Even as a child, the over-modest Mac had decided that he could never cut it as a pianist in New Orleans. As he remembered wondering, “How was I going to complete with killer players like Tuts Washington? Salvador Doucette? Herbert Santina? Professor Longhair himself? And the list only began there”. He had, even before his illness, agitated to take up the guitar. His long convalescence enabled him to air his plea with such incessancy, such vehemence, that his beleaguered parents finally gave in. He was sent for instruction to Werlein’s Music Store on Canal Street, already at that time a New Orleans institution and still in business today. His teacher soon sussed that Mac was going to be a difficult, if talented student. The instructor delivered a verdict along the line of, “Good ear, will never learn to read music”. The fancy, store-bought lessons ceased forthwith; but Mac was still hard at it.

He locked himself in his room for weeks on end, learning by ear the licks of his twin idols of the time: T-Bone Walker and Lightning Hopkins. “If I can’t make it as T-Bone, I’ll try Lightning, he told himself. His father, seeing that his son had a talent and drive, and being himself connected in the music scene, made a wonderful decision. He persuaded Walter “Papoose” Nelson to instruct his son.

Papoose was Fats Domino’s lead guitarist (and the son of Louis Armstrong’s lead guitarist) and had long been a hero to Rebennack. As Mac recalled: “The first lesson, Papoose listened to my chops and said ‘Hey, man, you can’t play that shit and get a job. What are you, crazy? That outta-meter, foot-beater jive. You gotta play stuff like this’. Then he started playing legitimate blues, which I was on the trail of with T-Bone Walker. It was the Lightning shuffle that was off the wall as far as Papoose was concerned”.

Papoose’s primary contributions to Mac’s musical education were twofold. First, it was Nelson who finally won Mac over to the benefits of learning to read music. Second, to impart musical discipline, Nelson would force Mac to play rhythm guitar for hours on end, never allowing him a solo.

Mac’s next teacher, Roy Montrell, also imparted a valuable lesson. To his first lesson with this new teacher, Mac bounded in with his brand new guitar, “a cheap but flashy-looking green-and-black Harmony”. Roy took at the guitar and (said) ‘Why’d you bring this piece of shit over here?’ ‘It’s my guitar’, I said. ‘Give me that guitar’. He took it, walked outside into the backyard, laid it on the ground, picked up an axe, and split it right in half. Then he broke it in pieces and threw it in the neighbour’s yard”.

That done, he called Malcolm Rebennack Sr. on the phone and arranged for Mac to come back next week with a second-hand Gibson, an axe that Mac found himself working overtime with his father to pay for.

By the time Mac was on the cusp of his teens, he was a somewhat streetwise musician, hanging out in black clubs and scoring drugs in the projects for his older “junko partners”, or drug-buddies. Soon he was smoking pot himself, and in due course he progressed to pills, coke, and eventually junk. All the while, he was attending the south’s most prestigious Catholic high school, New Orleans Jesuit. In class, he daydreamed and wrote songs, which he would deliver to the offices at Specialty Records, and plotted gigs with several high school bands. Something had to give, and as one can imagine, it was school. He dropped out a year of graduation and later, while in prison, obtained a correspondence course diploma.

Not that in his lines of work he needed any such qualification. Soon he was a fully-fledged constituent of the New Orleans underworld. In addition to his burgeoning songwriting work, his session playing, and road gigs both local and regional, Mac attempted half-hearted sidelines such as pimping, forgery, and as an auteur of pornographic movies. His running buddies included street characters with names like Opium Rose, Betty Boobs, Stalebread Charlie, Buckethead Billy, and Mr. Oaks and Herbs. Meanwhile, he entered into a star-crossed, drug-sodden marriage to Lydia Crow. Lydia, though no shrinking violet herself, did attempt to go straight from time to time. But Mac would hear nothing of it, and their marriage ended by 1961.

His personal life a shambles, Mac’s professional life was faring better. He was kicking serious ass in the studio, and it is his guitar one still hears today on Professor Longhair’s, “Mardi Gras in New Orleans”. Mac-penned tunes like “Losing Battle” (a hit for Johnny Adams) and “Losing Battle” (recorded by Jerry Byrne) (the same song?) were just two of his fifty compositions recorded in New Orleans between 1955 and 1963. But (as is well-known today) the record companies of the 1950’s were not exactly ready coughers-up of royalties, so most of Mac’s compensation came from his sessions, gigs, and mostly ludicrous street tough sidelines. One such example of the corruption of the New Orleans music business of the ‘50s will suffice. Rebennack wrote a song entitled, “Try Not To Think About You” which languished unrecorded in the offices at Specialty Records for a while. Unrecorded, and more importantly, uncopyrighted. It eventually came to the attention of Lloyd Price, who changed the title to “Lady Luck”, switched record labels, and changed the composer’s name to - you guessed it - Lloyd Price. It would have been Rebennack’s biggest hit up to that date. After literally stalking Price, gun in hand (Mac planned on wasting him backstage after a show) for some time, he finally cooled off and chalked it up to bitter experience. An absurd coda ensured, when Rebennack’s parents unknowingly hired Price’s own attorney to sue Price for the royalties from “Lady Luck”. The lawyer, Mac related, “pocketed the change and did nothing. for a minute, I was afraid if I ever ran across that bastard, I’d kill him, too”.

Such chicanery aside, New Orleans of the 1950s was a paradise for musicians. Always a wide-open town (by American standards), the Crescent City was never more raucous and hard-partying than it was then. Gigs abounded in the all-night bars, bordellos, tourist joints, society haunts, and neighborhood taverns. That Rebennack was far ahead of his time regarding race helped him find work, but also earned him some less-enlightened enemies on both sides of the color line. He began to run into flak from the two musician’s union (one black, one white) for having the temerity to play with opposite-hued musicians.

Eventually these unions and the crusading, publicity-seeking New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison were to conspire to run Rebennack and most of the rest of the New Orleans music scene right out of town. The union began levying exorbitant fines on Rebennack (officially for playing scab sessions) and blacklisting record producers (like the legendary Cosimo Matassa) who dared to buy the latest equipment. Their short-sighted thinking was that new equipment would equal less studio time instead of more polished records and bigger hits. Garrison, for his part, launched a crusade on vice which closed down the thriving whorehouses and gambling dens, both important sources of income for both the music and tourist industries.

Rebennack’s troubles were only beginning. A fracas with a Jacksonville, Florida hotelier resulted in Rebennack getting the ring finger shot nearly off his left hand. Doctors reconstructed the finger to a degree, but not to the point that would enable him to resume making a living with a guitar. He was forced into playing bass with the tourist-oriented French Quarter Dixieland bands, a gig that convulsed him with boredom. He sank deeper than ever into heroin, and it was then that his marriage ended. To top it all, he was busted by Garrison’s goons for heroin possession, a charge that was to send him eventually to a Federal prison hospital in Fort Worth, Texas. There he served as a guinea pig for the various and infamous rehabilitation experiments then -as now - rampant in the land. He was released embittered but not in the least rehabilitated.

He returned briefly to New Orleans and was given some pointers on the organ from Crescent City keyboard maestro James Booker. However, he soon soured on Garrison’s Brave New Orleans and at the invitation of an old friend (saxophonist/arranger Harold Battiste) flew out to Los Angeles. A contingent of New Orleans musicians had already set up shop in the City of Angels, and Rebennack fell quickly to work doing studio odd jobs under the auspices of Battiste. Battiste was the brains (ahem) behind Sonny & Cher, and was a close associate of Phil Spector. Battiste mortared Rebennack in on some of Spector’s sessions, but Mac did not enjoy being just another brick in the ‘Wall of Sound’. He called it, “a monument to waste with echo all over the place! It was just padding the payroll, as far as I could see”.

He held down a brief stint as Frank Zappa’s pianist, but found that stultifying as well. This gave him an entrée into the acid rock world, in his words, “all these little acid groups springing up like mutant fungus after a chemical spill”. He attempted to work with Iron Butterfly, whom he termed “Iron Butterfingers” and Buffalo Springfield to little if any effect. A frustrating term as in-house producer with Mercury Records followed, but Rebennack and his cohorts suspected that it was just a tax dodge. He was more musically frustrated than he had ever been in New Orleans, and his drug woes continued unabated. As a parolee, he was under the watchful eyes of a great many government agencies as well. But slowly, the concept was forming that was to take him to heights he wouldn’t have dared dreamt possible.

Growing up in New Orleans, Rebennack had eagerly immersed himself in the City’s myriad native traditions and home-grown Afro-Latin religions. He himself was a half-hearted practitioner of gris-gris, New Orleans’ own unique branch of the voodoo tree. In his avid studies of the history and religion of the city, he had thrilled to the stories of John Montaigne aka Bayou John aka and most frequently, Dr.John. John was a Senegalese of self-proclaimed royal lineage who had been taken from Africa by slavers to Cuba. There he won his freedom, and shipped out as a sailor before eventually choosing to settle in New Orleans. He set up shop as a shaman, telling fortunes, healing, and selling a cornucopia of hexes. He was good at his job, and eventually prospered to the point where he even owned slaves himself. The kicker for Rebennack was coming across an account of a 19th Century vice bust in which John was arrested with one Pauline Rebennack for voodoo-related offences and suspicion of operating a whorehouse. For years, Mac had felt a spiritual kinship for Dr.John, and this account raised the quite possibility that one of his family had had the same feelings.

Even so, the idea that Rebennack had been ruminating cast his friend Ronnie Barron in the roll of Dr. John. But when the project was finally greenlighted, Barron had other contractual duties and Rebennack reluctantly assumed the mantle himself. Between Sonny & Cher sessions, virtually on the sly, Rebennack recorded the “Gris Gris” album with a band of New Orleans natives. Atlantic executive Ahmet Ertegun was at first displeased with the move. “Why did you give me this shit”?, Rebennack remembers Ertegun bellowing. “How can we market this boogaloo crap”? Eventually the canny Ertegun sniffed something in the late-’60s zeitgeist that could enable an off-the-wall act like Dr.John to sell, and he (to Rebennack’s surprise) released the album.

On “Gris Gris”, Rebennack played very little keyboard, contributing only organ parts on two tracks (“Mama Roux” and Danse Kalinda”). His aim was to introduce America to New Orleans’ mystical side, and also to “let us musicians get into a stretched-out New Orleans groove”. The album sold well enough to appease the suits, with very little backing, and meanwhile Rebennack’s fertile mind was cooking up a killer road show. Drawing on the venerable southern minstrel tradition and the pageantry of the Mardi Gras Indians, Dr.John and the Night Trippers’ road show boasted snake-festooned dancers, magic tricks, and costumes manufactured from the carcasses of virtually every living creature that ever crawled, slithered or flew in the bayou country. As Rebennack recalled, “When this stuff started coming apart in pieces, I had to start hanging around taxidermy shops big-time, scavenging new material.”

He and his similarly attired band of New Orleans roughnecks unleashed this act the acid-drenched southern California of 1968 to no little astonishment. But by the time “Babylon”, the Night Tripper’s second album came out, the band began to dissolve. Rebennack (along with the most of the rest of America) felt the end time was at hand, as the title implies. The album reflects Rebennack’s chaotic personal life - his drug use and police persecution, his dissolving band -- and the state of American life in 1968, a year in which it seemed that violet revolution was at hand. It was a year in which both Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King fell to assassins, riots consumed black ghettos in flames from Miami to Watts, and the Vietcong launched the ferocious TET offensive. The album features odd time signatures (11/4, 5/4,10/4), doom-laden lyrics, and hybrid Afro-Caribbean/avant-garde jazz feeling. As Rebennack later said, “ It was as if Hieronymus Bosch had cut an album”. Who better to chronicle those disorderly times?

Things were about to get extremely untidy for Rebennack again, as well.

While touring in support of “Gris-Gris”, the Night Trippers had been busted in St. Louis, and Rebennack as frontman shouldered the load. A lawyer arranged a deal in which Charlie Green (the manager of Sonny & Cher and Buffalo Springfield) was to pay off the St. Louis bail bondsman. The bondsman, unbeknownst to Rebennack, never collected. Green and partner Brian Stone then confronted Rebennack with the proverbial “Offer you can’t refuse”. Since he had gotten Rebennack sprung, Green put it to Mac, we get to manage you from now on. Rebennack, frazzled, saw no alternative.

Green proved to be the worst of all managerial archetypes, the would-be star. Mac recalled, “He thought of himself as the star and me as the roadie of the operation. Even though I wasn’t on no kind of star trip or nothing, I didn’t want my manager hanging around, running some kind of Jumpin’ Jack Flash number and trying to upstage me. Beyond that was the basic problem: a drugged out band hooked up with a starry-eyed manager results in a chemically unbalanced situation and, in general, a fearsome sight to behold.”

While at work on “Remedies”, the third of five of Rebennack’s Atlantic releases, Green and Stone persuaded Rebennack to check himself into a loony-bin, with an eye toward having him declared incompetent. This move would allow them to help themselves to a slightly higher percentage of Rebennack’s earnings than their current 25%, something more along the lines of 100%. Rebennack quickly wised up, escaped from the asylum, and exiled himself to Miami. Meanwhile, the managers had released the unfinished “Remedies” album. One of Rebennack’s chief aims for the album was to spread the news about Louisiana’s notorious Angola Farm, then as now America’s most deplorable and inhumane prison. Rebennack, incommunicado in Miami, was thus unable to put wise the Rolling Stone reviewer who took his lament Angola Anthem to be a protest song about the nation of Angola.

A disastrous European tour followed, one in which was Mac was hamstrung by a third string band (most of the Night Trippers were unable to get visas). The tour was augured in by Mac from backstage the electrocution death of the Stone the Crows guitarist Les Harvey at a festival. At Montreux, his bass player without warning dropped his bass and brandished a trombone which he had concealed in the wings, and proceeded to (Rebennack related) “start dancing around the stage, playing Pied Piper to the audience’s mountain villagers”.

At the end of this arduous road, Mac headed for London to round up session players for the album “The Sun, Moon, and Herbs”. Graham Bond, Eric Clapton, Ray Draper, Walter Davis Jr., Mick Jagger, Doris Troy, and a battery of drummers from virtually every West African and Caribbean country were on hand for a days-long, Opium and hash-fuelled epic of a session. He delivered the finished article to Green for post-production work a happy man.

Some weeks later, Rebennack returned to find his beloved album chopped, diced, and filleted by Green. Material was added and deleted, more was overdubbed. Most of what Rebennack felt was the best music was simply gone. In addition, it came to his attention (when he was alerted to a pair of bounty hunters at his doorstep) that Green had not, in fact, bailed him out of anything. Green was summarily dismissed, and Rebennack and some engineers endeavored to salvage what they could of the “Sun, Moon, and Herbs” album.

He signed next with manager Albert Grossman, of Joplin, Dylan, and The Band fame. He was the manager who “electrified” Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival, which touched off a brawl between himself and folklorist Alan Lomax in front of several thousand bemused folkies. Lomax, though, was not the only one in the music scene who wanted a piece of Grossman. Soon enough, Grossman and Rebennack came nearly to blows. Grossman’s style was to play it cool with his artist, while his “bad-cop” flunkie Bennett Glotzer delivered such news as, “Thanks for signing with us. We now control 1/3 of your publishing”. Glotzer and Rebennack had two punch-outs, and things got so bad that Rebennack turned to his native gris-gris. He would each day leave a dead bird on Glotzer’s doorstep, surrounding by black candles and sprinkled with “goofer dust”. Eventually, this hell-broth boiled over when, in a tête-à-tête with Grossman, an enraged Rebennack snatched Grossman’s beloved peyote button, a pet psychedelic Grossman had been nurturing for three years, and devoured it, skin, pulp, stem and all, in front of his very eyes. The relationship dissolved into a maelstrom of threat and counter-threats, and now Rebennack had not one, but two oddball ex-managers scheming for his destruction.

Somehow, Mac found the time to sit in the Rolling Stones’ “Exile On Main Street” sessions, and also to record one of his best albums ever. (While in the studio with the Stones, he discussed with them his and New Orleans songwriter Earl King’s idea for an album of dirty blues tunes. Back in the fifties, when he played the after hours joints, he had often played for an audience of street characters x-rated versions of old blues tunes. The Stones demurred, but later released “Cocksucker Blues” on their own, which irked Rebennack. He felt that since he had given them the idea, he should be compensated) His own effort produced “Gumbo”, an album steeped in the New Orleans of his youth. Featuring covers of songs by King, Professor Longhair, and several other lesser lights of that time and place, the album was his most direct tribute to his home turf to that date. To back the album, Mac ditched the voodoo shtick he had employed on the road since 1967 in favour of a revue format. As Mac termed it, he had “enough of the mighty-coo-de-fiyo hoodoo show”. The Gumbo tour, backed heavily by Atlantic, reached Carnegie Hall and other such bastions of the high life, and a single, ”Iko Iko”, cracked the top 40.

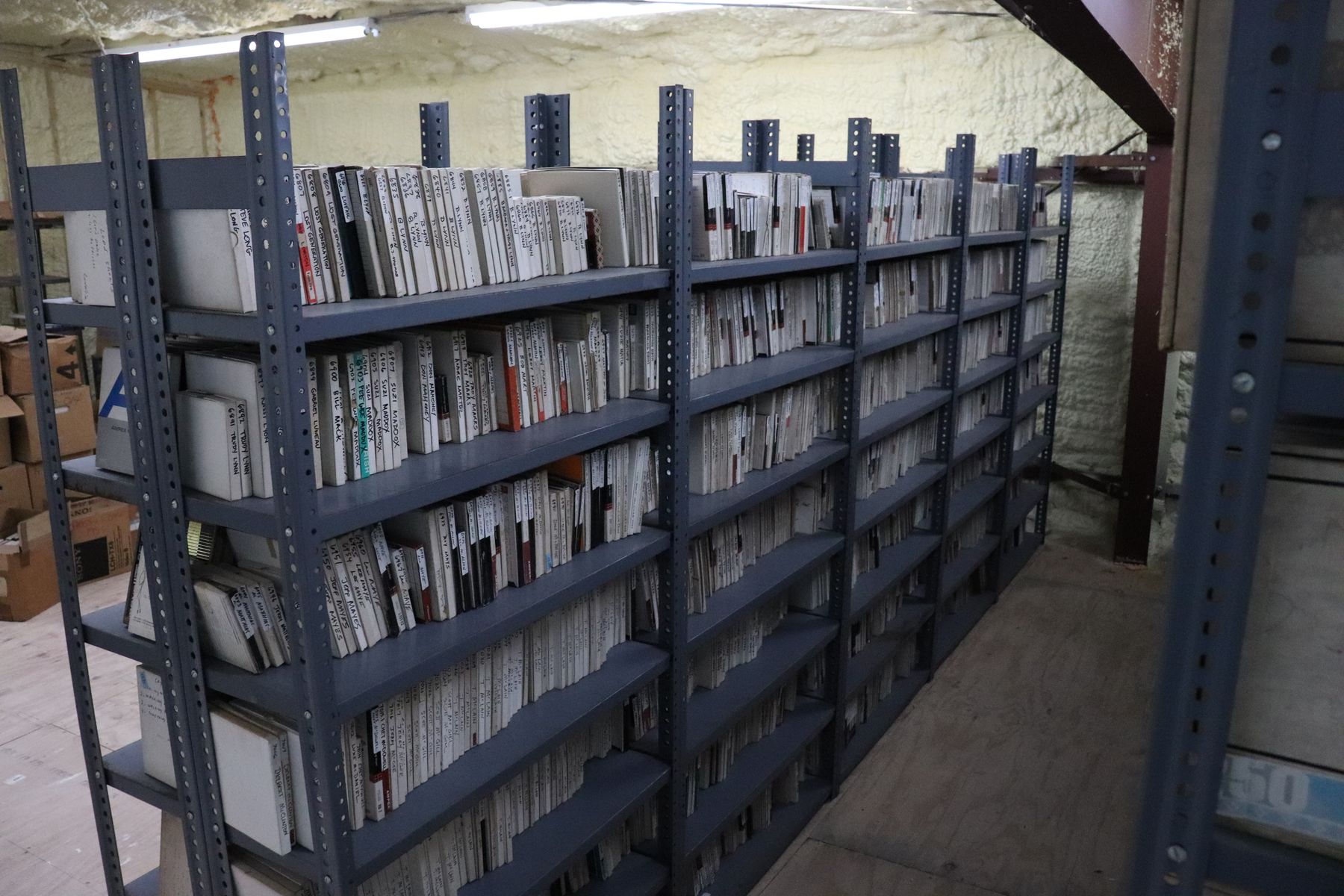

The dark cloud to this silver lining was that hard on the heels of his chart success, several of his past employers saw fit to release albums of demos. Among them were Green, Huey Meaux (with whom Rebennack had worked as a session producer) and an unknown cast of characters. This very collection is one such unfinished product.

Meanwhile, Rebennack had seen fit to employ yet another volatile, less than 10% straight forward manager. Phil Walden, who had hit the big-time managing Otis Redding was then cresting on the Allman Brothers doomed wave, and he also handled Rebennack’s New Orleans chums, The Meters. Clearly Rebennack thought, here at last was a manager with the Midas touch. In 1973, Rebennack and the Meters hit the studio together to record “In The Right Place”.

At first, things with Walden and the album went swimmingly. Walden booked Mac and The Meters on some Allman tours, on which Rebennack enjoyed himself immensely, both professionally and personally. The album scored him both his biggest hit (the title track) and perhaps his most enduring composition. “Such a Night” is a stone-cold classic, a song that sounded as old and enduring as music itself from the very day it was waxed. This writer was astonished to learn that it was written by Rebennack in 1973, as I had always assumed it emanated from Cole Porter or some such.

The relationship with Walden, which had been going so well, came to a screeching halt when Rebennack returned home road-weary to find his house bereft of furniture, furniture that had somehow found its way across town to Walden’s recording studio. It was this move that finally put an end to Rebennack’s reliance on anyone else to handle his business affairs. Since then he has managed himself.

Later in 1973, a collaboration with white bluesman John Hammond Jr. and Mike Bloomfield brought forth the “Triumvirate” album. Meanwhile, Rebennack embarked on a tour of shows benefiting the Black Panthers, which, he recalled, “had the immediate effect of bringing serious federal heat down on our asses! I discovered that we’d jumped into a whole new level of criminality. We weren’t garden-variety dope fiends any more; now we’d become political activists, the most fouty-knuckled lames of them all”. The year ended with Rebennack attempting to aid a drink- and coke-addled John Lennon make the album “Rock ‘n’Roll” with Rebennack’s old boss Phil Spector. As active and fruitful as 1973 seemed (in addition to the above there were sessions with Harry Nilsson and Ringo Starr), Rebennack was still broke and very bitter. He seriously pondered retirement, and had developed a reputation as a pain in the ass.

The rest of the early seventies passed by in a blur of drug abuse and fallen sidemen. James Booker, the classically trained, extremely eccentric genius of the New Orleans keys, came and went from Rebennack’s band several times, before dying of a cocaine overdose in 1983. Ray Draper was whacked by New Jersey loan-sharks. Percussionist Albert ”Didimus” Washington was killed by a Cabbage-juice diet designed to heal his ulcers. As the seventies wore on, though, things very slowly began to turn around for Rebennack.

A collaboration with legendary New York songwriter Doc Pomus (“Save The Last Dance For Me”, “Lonely Avenue”, “Suspicion”), produced the song “There Must Be A Better World Somewhere”, which B.B. King later picked up and won a Grammy. Tommy LiPuma persuaded Rebennack and Pomus to sign with his A&M-affiliated Horizon label. “City Lights”, the label’s second release, quickly followed. The album is something of a semi-autobiographical rock opera, co-written by Rebennack, Pomus, and Henry Glover (“ I Love You, Yes I Do”; “Drown in My Own Tears”) concerning the exploits of some ex-pat New Orleanians in the Big Apple. “Tango Palace”, another Mac-Pomus offering, came hard on the heels of “City Lights”, but not soon enough. The label foundered almost immediately after “Tango’s” release. Rebennack recalls the interlude with Horizon, during which he also gigged with 50’s R& B legends Hank Crawford and Fathead Newman, as being rewarding musically, if not commercially.

In 1980, Rebennack began an association with Jack Heyrman’s Clean Cuts label. Heyrman persuaded Rebennack to confront a personal bugaboo and record two albums of solo piano and vocals. Rebennack had always had nightmarish visions of this being his end, that “I’d end up a solo-piano lounge act, staring at Holiday Inns or bowling alleys for the rest of my natural life”. Nevertheless, two Clean Cuts releases, “Dr. John Plays Mac Rebennack” and “The Brightest Smile In Town”, ensued. On them, Rebennack erased the last vestiges of the Gris Gris act and tackled some more sophisticated and older forms of music. He wanted to appeal to “a spiritual awareness, not just that low-down meat level”, but hastened to add that, “The hardest thing to do is let the spirituality flow and turn the meat on. Doing that is creating art, radiating the 88’s”.

Rebennack expanded on this with 1989’s “In A Sentimental Mood”, a collection of classics this time presented in a combo format. A duet with Rickie Lee Jones on Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson’s ”Makin’ Whoopee” took home the Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Duet, and the album was one of the top-selling jazz albums of the year. Two more albums in a jazzy vein, “Bluesiana Triangle”, cut with Fathead Newman and the great Art Blakey; and “Bluesiana II”, cut again with Newman and others followed in the next two years.

In 1989, Rebennack ended his 34-year relationship with heroin, and three years later released “Goin’ Back to New Orleans”, one of his most ambitious projects to date. Like “Gumbo”, “Goin’ Back” is solely a New Orleans affair, but it takes a much broader approach. Songs dating as far back as 1850 were recorded, with each of the ensuing cuts representing a stylistic breakthrough that has occurred since then. There’s a Mardi Gras Indian tune, homages to Jelly Roll Morton, Buddy Bolden, Louis Jordan, Professor Longhair, James Booker, and Fats Domino. The Neville Brothers, Wardell Quezergue, Al Hirt, and Pete Fountain, among a great many others turned out in support of the project. Any one volume CD that endeavors to cover 150 years of music from America’s most tuneful of cities is bound to fail, through as Rebennack says, “ the only thing that can beat a failure is a try”. Ultimately, the album ranks in the top 5% of all New Orleans releases, a too-brief primer lovingly and excitingly presented by the best musicians the city had to offer at that time. By turns wistful, violent, joyous and tragic, it never loses the twin hallmarks of the city that birthed it - a sense of humour at the absurdities of life (and death) and some of the world’s most pulsating rhythms.

In 1994, Rebennack wrote with co-author Jack Rummel the excellent autobiography, “Under A Hoodoo Moon”. From it most of these notes were cribbed, and though this has proven to be by far my most verbose liner-note project, not one tenth of the story is yet told .

Far from being a typical rock & roll, ghost-written autobiography, it is a hilarious, tragic, brutally honest, and inspirational tale of one erudite and talented man’s struggle to make some good music in a country in which this has become increasingly difficult. The chapter in which his reminiscences of Professor Longhair are recounted in side-splitting detail is alone worth the price of the book.

The rest of the mid-nineties saw Rebennack’s voice become seemingly ubiquitous on American television, singing the praises of Wendy’s Hamburgers, among many another strange fruit from his American orchard. He has released several anthologies and two albums of new material - “Television” on GRP in 1994 and “Afterglow” on Blue Thumb in 1995. Any questions regarding this bizarre genius’ contemporary relevance were abolished in 1991 and 1993 when P.M. Dawn and Beck, respectively sampled his “I Walk On Gilded Splinters” for their own recordings, with utilising the Doctor’s tune in his breakthrough anthem, “Loser”. In 1997 he recorded a smoking duet with B.B. King on his collaboration with Doc Pomus, “There Must Be A Better World Somewhere”. He continues to tour and record, and still there is no bowling alley or Holiday Inn big enough to hold the audiences that pay to see him.

Like the city he came from, Mac Rebennack is a survivor. So is the music that they share. That indefinable blend of French, African, Caribbean, Spanish, and American ingredients, that gumbo of a city and a sound, the certain je ne sais pocky way hollers out Crescent City, has no living acolyte truer or more faithful than Rebennack. Long may he ramble!

~John Nova Lomax, November 1998